Shelley Winters

An Interview

By Harry Governick

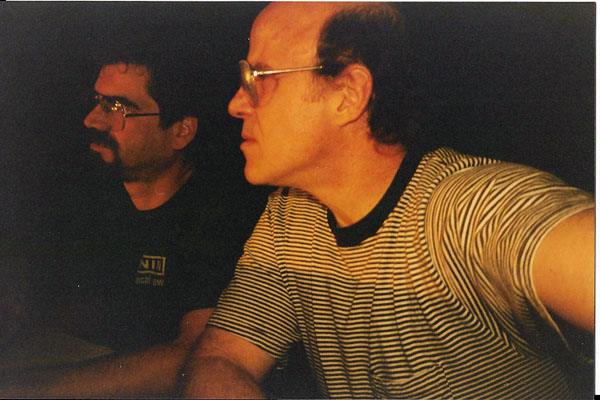

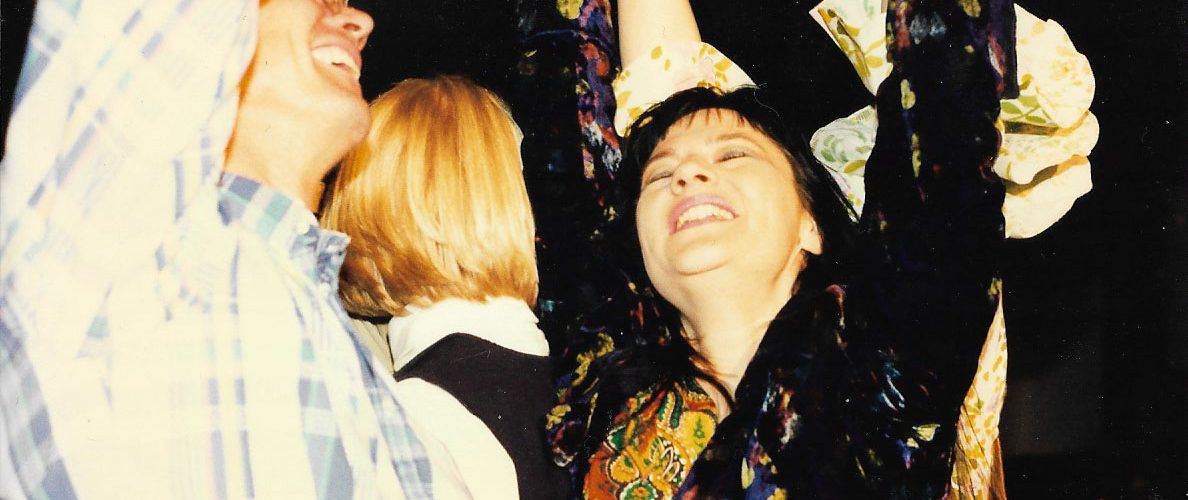

Foreground: Alberta Murphy (the author’s mother), Shelley Winters and Melissa Mayo (the author’s wife). Background: The infamous and notorious Walter Peterson.

This photo was taken in 1992 at Blueberry Hill Pub and Restaurant, sponsor of the St. Louis Walk of Fame Ceremony in St. Louis, Shelley’s hometown.

As you can imagine, Shelley’s schedule was tight, with family here, and much to do with her limited time.

If you haven’t read Shelley, Also Known As Shirley (William Morrow & Company) or Shelley II , then read them. Actors and others will gain valuable insights about the human condition from the gifted actress who so beautifully demonstrated that condition through her life in art.

I first met Shelley Winters in her private class at the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute in Los Angeles, in 1975. Although I had an impression from her talk-show appearances that she seemed less than coherent at times, that myth was instantly shattered the first day of class. There I discovered a woman of extreme intelligence and wit, and a loving and generous taskmaster who places art and its attending discipline at the top of the actor’s priority list.

Her search for truth in art is uncompromising. I have seen actors left “emotionally and psychologically naked” on the stage, devastated, curled up in an hysterical, primal puddle of tears, radiating self-doubt after listening to Shelley “critique” a scene performed in her class. After the tears would evaporate, Shelley would say, ” Call me at home, honey, if you have problems.”

An outsider might think Shelley is unecessarily cruel at these times. Insiders know that she always addresses the truth, regardless of how unpleasant it may sound, because Shelley knows that the business of the actor is much harsher than she will ever be, and to sugar-coat a critique of an actor’s performance does more harm to the actor than good.

Shelley herself was a sobbing “victim” of Lee Strasberg, who knew that the only way to free up talent is through exhaustive, brutally honest examination of the actor’s own “instrument”. Without this courageous exploration, the actor can become good, but seldom great.

After fourteen years since I took her private class, Shelley could not remember my name. This was no insult. Shelley often could not remember many names, because she had met tens of thousands of people during the course of her lifetime, many of whom “wanted something” from her.

One day in Shelley’s class at the Actors Studio-West, I performed a monologue from David Rabe’s The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel. Afterward, obviously deeply affected by my performance (I’m still humbled by the experience), a teary eyed Shelley asked, “What was your name again, honey?” When I told her, she said, “I’ll never forget it again.” She didn’t. I’m most grateful to have been considered a close friend of this highly gifted artist and beautiful spirit.

The Interview

September, 1992

HG: Shall we get started?

SW: Yeah. And you know, I think you ought to organize a class there [St. Louis].

HG: I tried that five years ago here.

SW: Yeah? And it didn’t work?

HG: I asked people to do certain exercises, and they refused, because they didn’t want to get that personal.

SW: Oh, then forget about it, I’m sorry.

HG: And they would bring dogs to class, and spend a lot of time socializing.

SW: Forget it.

HG: I did have three or four people who were, uh…

SW: Serious?

HG: Very serious. They call me even today, wanting me to form another one.

SW: You should have a master class, do the work of Stanislavski and Strasberg.

HG: I’d love to. I need it for myself. I can’t find it anywhere here. Would you be interested in doing a play here?

SW: Maybe, honey. Right now I can’t plan it. I’m going to do this class in June, and then I’m going to Los Angeles for work. I don’t think I would do eight performances a week, Harry. Maybe I could do Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday. You know. Alright, let’s go on with my interview.

HG: What is “talent”?

SW: Oh, boy. You start with a nine hundred dollar question. A nine MILLION dollar question. It’s very hard to define, and when it will mature. It’s not just a love of theatre. That’s part of it, but for instance, do you know who Ron Rifkin is?

HG: Yes.

SW: He’s fifty-three, and he just opened in The Substance of Fire by a new playwright, Jon Robin Baitz. Now, before he did this play, I don’t know what Ron Rifkin did, do you?

HG: I know I’ve read his name in the “T.V. Guide” for doing movies of the week, and things like that.

SW: Yeah, he’s done little parts here and there. No leads, that I know of. If he has, I don’t know. I think he did a, uh, series, and suddenly he’s brilliant. Now he’s worked in the “method” for thirty years, he’s been in the Actors Studio since the late sixties. That was also true of Jack Klugman. I tell the story about him. He was playing little parts, and gangsters, and he gambled a lot, and he did A View From The Bridge at a little theatre in Hollywood, and he was ready. But you have to… you see, people don’t realize… a painter keeps painting, a composer or pianist or violinist practices. It’s very hard for actors, because unless you have a camera or stage, where do you practice?

HG: Right.

SW: And it’s an art that has to be practiced. That’s what’s so extraordinary about the Actors Studio. It’s one of the few places in the world where actors can keep their tools sharpened. Maybe it’s the only place, I don’t know.

HG: I think it is, in my experience. [Now there’s TheatrGROUP]

SW: England has a lot of repertory companies. Every town has a repertory company. And they do good plays, you know, Shakespeare, with a lot of people. They can afford it, it’s subsidized by the government. I’ll tell you a quick story Lillian Gish told me. When the war was over, and she was either in Munich or Berlin, I’m not sure, she saw men rebuilding the Opera House. And the next day she saw an American General, or something, and she asked why they were allowing them to rebuild the Opera House. They need hospitals and homes and everything. And the man said, ” In their viewpoint, art is as necessary as a home.” And we don’t have that attitude, and unfortunately, television is eroding the concentration and the appetite. I see, and I hear that people play all over the country here. I mean, really well known, you know, not movie stars, but well known stage…The Cleveland Playhouse, The Washington Arena. There seems to be theatre all over the country. It’s too expensive in New York.

HG: Yeah, Ray Walston went to Arizona to do Damn Yankees last year.

SW: Yeah? So things are happening. But I think you gotta make them happen somehow. You gotta make them happen.

“I think everything you are, you show when you act.”

HG: What advice would you give to those starting out in a career in acting?

SW: I think everything that you are, you show when you act. And you have to work on yourself. You have to read a great deal, you have to go to museums. You have to understand, a man who wears a sword walks differently than one who doesn’t. You have to have a sense of period costumes, how they can change people’s bodies and minds. That’s where characterization comes in. And if you really love it, don’t give up. And the important thing is to work. And you should finish University. It’s very important. Not just that you work in the theatre there, or drama classes, but you get a wide experience of literature, and all the plays that have been written, and the whole history of theatre. It’s very important to study from the Greek. You know, there’s a reason they wore masks. I mean, the things that Socrates and Aristotle and Plato talked about are still relevant today. More, maybe.

HG: What are the main obstacles you find teaching actors?

SW: It’s different for different people. They want instant fame now. It takes twenty years to make an actor. You have actors who are flash in the pans, but to make a good career, that you can act all your life, it takes twenty years of training, and work in Summer Stock and Winter Stock, and small parts, and television movies. Maybe Rock and Roll is instant, but even that takes experience. Youngsters don’t really understand that that’s what it takes. I mean, an actor who has proficiency, and timing, and the ability to reveal themselves, the willingness. You act with your scars.

HG: You once told me that you had trouble doing Sitcoms, and yet I saw you on “Roseanne” as her mother.

SW: (laughs) Grandmother. I used to because it took me quite a while to understand that it isn’t on a deep level. It’s because I’ve been trained to be on a deep level, and I’m habituated to working deeply, it’ll happen anyway. But I felt it was very instant, and they rewrite up to the last minute. I had to develop an attitude that, uh, not to care that much, and have fun. The most important thing is to have fun, and the audience will have fun. They’re like a vaudeville sketch. That’s the closest thing I could compare it to. It’s not like acting in a play. It’s twenty-four minutes, and it’s like a sketch for vaudeville. And you’ve gotta develop that kind of attitude. But then it’s funny.

HG: Have you ever worked with a director whose ideas were radically different from your own, and if so…

SW: Oh, often, honey, and you gotta find out from what he says, what he means. You gotta figure out what he wants. He may use a different lingo than you, or different speech. One of the greatest directors I ever saw was Charlie Chaplin. I talk about it in my book. His idea of directing was to show you. And he could do it better than anybody else. He directed his son in What Every Woman Knows.

HG: Did you actually watch him?

SW: Yes. I watched him direct. And he could become a woman, or a man, or a tall, or a little man, or a child. And he could do it better than everybody else. So you have to figure out, not to imitate him, but to figure out what he wants from the part. So it’s the actor’s obligation to figure out from the way… you know, sometimes directors, especially casting directors, will say, “Be angrier here, or sadder here,” you know. That’s what soap opera is. They’re bad, glad, sad, mad, you know? Dead! (laughs) So you have to have enough technique and experience to adjust to what results are wanted by the director and the writer.

2 thoughts on “Shelley Winters Interview-Part 1”

I am a lifetime member of the Actors Studio and worked with Shelley Winters on her play “Noisy Passenger.”

Your interview with her makes me miss the Actors Studio and Amerika. Currently I reside in Amsterdam, conducting workshops throughout Europe .

My website is methodactingteacher.com. Thank you for your Inspiring website.

Thank you for the response to my interview with Shelley Winters. Knowing Shelley as I did, it must have been a wonderful experience working with her on a play. Yours is the very first comment i’ve approved at any page of TheatrGROUP’s extensive site, and made your webpage link active. We wish you all the best in your life in art. ~Harry Governick / Melissa Mayo